Psychological Misconceptions and the Dunning-Kruger Effect

Place caption here

Abstract

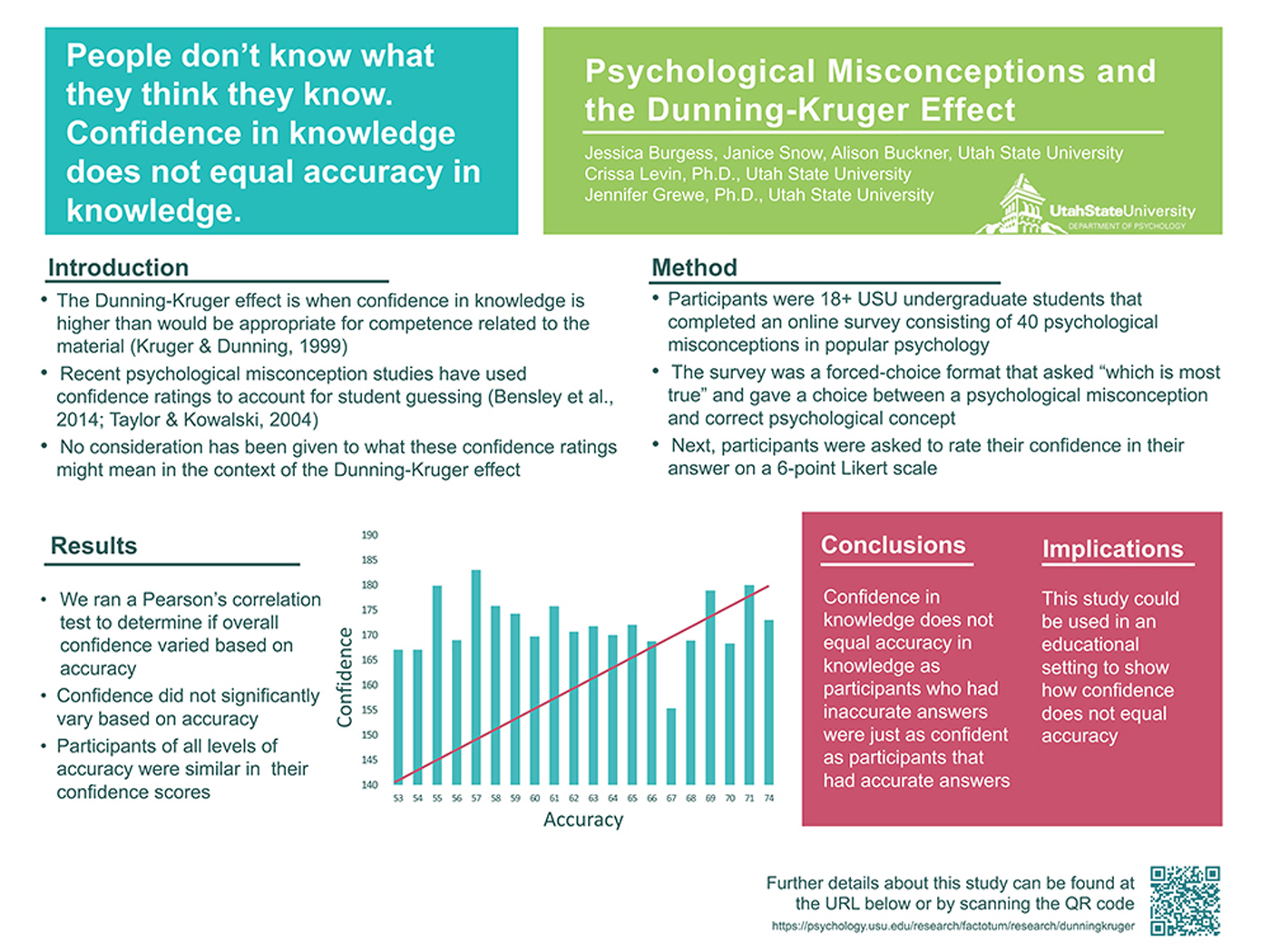

Psychological misconceptions are commonsense beliefs about psychological topics that are inaccurate and unsupported by scientific research. The Dunning-Kruger effect is when confidence in knowledge is higher than would be appropriate for competence related to the material. Past studies of psychological misconceptions have used confidence ratings to account for guessing. No consideration has been given to what these confidence ratings might mean in the context of the Dunning-Kruger effect. We looked at how confidence relates to accuracy with regards to the Dunning-Kruger effect by administering an online survey containing a forced-choice between 40 psychological misconceptions and the alternative true psychological concepts. Participants (n=185) rated their confidence in their answers on a 6-point Likert scale. We found that participants of all accuracy levels on the misconceptions test were similar in overall confidence levels, meaning that people who were least correct were just as confident as those who were most correct. Participants who were in the top 25 percent of accuracy on the misconceptions test were more likely to have lower confidence in wrong answers. Participants in the bottom 25 percent of accuracy were more likely to be more confident in their wrong answers than their correct answers on the misconceptions test. Overall as accuracy went down, confidence in wrong answers went up.

Keywords: Dunning-Kruger effect, psychological misconceptions, unskilled and unaware, undergraduate students, psychology students, confidence

Literature Review

Psychological misconceptions are defined by Bensley and Lilienfeld (2015) as “commonsense beliefs about the mind, brain, and behavior that are held contrary to what is known from psychological research” (p. 283). Belief in misconceptions can cause harm or impede learning (Taylor & Kowalski, 2014). The misconception that vaccines cause autism, for example, has caused harm to the public by lowering rates of immunization which puts children at risk (Kolodziejski, 2014).

Researchers have been studying the prevalence of psychological misconceptions for more than 80 years. Findings from these studies have found that psychological misconceptions are present in the general population as well as in educators, undergraduates, and graduate students (Hughes, Lyddy, & Kaplan, 2013). Strongly held false beliefs can be difficult to change. The more strongly a belief is held the more it gets in the way of comprehending new material that could contradict or correct the belief (Taylor & Kowalski, 2004).

Many misconception studies have used a True/False format in which all answers are false (Furnham, 1992; Furnham & Hughes, 2014; Hughes et al., 2013; Taylor & Kowalski, 2004). This could potentially be a limitation due to participants finding patterns in the answers and guessing. Some studies have tried to fix this limitation by balancing the questions between true and false (Arntzen, Lokke, Lokke, & Eilertsen, 2010; Gardner & Brown, 2013). These studies have been criticized for ambiguity in their phrasing of the questions (Bensley & Lilienfeld, 2017; Hughes et al., 2013). Bensley, Lilienfeld, and Powell (2014) have proposed a forced-choice method of testing psychological misconceptions, which avoids the limitations with the True/False method and limits ambiguity by directing attention to the differences between the two statements.

The Dunning-Kruger effect is when confidence in knowledge is higher than would be appropriate for competence related to the material. For example, students who are unfamiliar with psychological concepts may be overly confident in answering whether concepts were accurate or not accurate (i.e., misconceptions; Kruger & Dunning, 1999). Recent psychological misconception studies have used confidence ratings to account for student guessing (Bensley et al., 2014; Taylor & Kowalski, 2004), however, no consideration has been given to what these confidence ratings might mean in the context of relative expertise of the content, and they have not been analyzed relative to accuracy in a way that would account for the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Previous research has found participants who make more errors on a cognitive reflective test overestimated their performance on the test (Pennycook, Ross, Koehler, & Fugelsang, 2017). This suggests that the participants who rate themselves as most confident may have more incorrect answers. Confidence and accuracy are related to the Dunning-Kruger effect, in the direction of a u curve, such that when accurate knowledge is low, confidence starts out high. Then as accuracy increases, confidence dips lower and then increases once again (Kruger & Dunning, 1999). Therefore, confidence should be related to accuracy.

Hypotheses

- We hypothesis that participant confidence of the misconception will vary based on participant accuracy on the misconceptions test.

- We hypothesize that participants in the top 25% and bottom 25% of accuracy will have higher confidence than those in the middle 50% of accuracy.

- We hypothesis that participants average confidence in incorrect answers will vary based on participant accuracy on the misconceptions test.

Methods

Survey

In the present study, we administered an online survey in REDCap using iterations of 40 of the 299 misconceptions from the book 50 Great myths of popular psychology (Lilienfeld, Lynn, Ruscio, & Beyerstein, 2010). We worded the questions to account for ambiguity and sensationalism in the myths as they were worded in the book. This was necessary given that the book provided further explanations to account for the single sentences, and in the study the participants only had access to the single sentences, requiring the need for clarity. Each question on the survey started with the phrase “Which is most true.” Participants had a forced-choice between the true or the false version of each of the 40 misconceptions. After each forced-choice item, we requested that each participant rate their confidence in the correctness of their answer for each question on a 6-point Likert scale.

Sampling

We will be dividing the participants into quartiles based on accuracy, leading to a total of 4 groups (0-25% quartile on the misperceptions test group, 26-50% quartile on the misperception test group, 51-75% on the misperception test group, and 76-100% on the misperception test group). We used g*power for estimating the appropriate sample size for now comparing 4 groups. To detect a moderate effect size for a one-way ANOVA, we anticipate needing a total of 280 participants (which would leave 70 per quartile/ per group).

Participants

Participants were recruited using USU’s SONA-system. The survey was estimated to take 30 minutes to complete. By completing the survey participants received .5 SONA credits. In order to qualify to take the survey, participants needed to be USU undergraduate students and be 18 years old or older.

Results

A Pearson’s correlation was conducted to determine if overall confidence varied based on accuracy. There were no statistically significant differences between confidence and accuracy, r(183) = -.087, p = .237. In other words, confidence did not change based on accuracy on the misconceptions test.

For our second analysis, we examined individual differences in confidence difference scores by assigning participants to their respective quartiles based on total accuracy scores on the misconceptions test. Confidence was split by accuracy so that confidence of correct answers was analyzed separately from confidence on incorrect answers for each participant. Next, we calculated confidence difference scores by subtracting participant’s mean confidence of wrong answers from their mean confidence of correct answers. This analysis yielded confidence difference scores in which positive scores indicated confidence in correct answers was higher than confidence in wrong answers. Negatives scores indicated that wrong answers received higher confidence scores than correct answers, and scores near zero indicated that there was little to no difference in the confidence of correct answers and wrong answers. A one-way ANOVA comparing quartiles on the confidence difference scores was significant, F(3,181) = 7.06, p < .0005, ω2 = 0.09. Post hoc comparisons revealed that participants in the top quartile (M = .38, SD = .45) had confidence difference scores that were significantly higher than participants in third quartile (M = .16, SD = .34), and were significantly higher than those in the second quartile (M = .17, SD = .35), and were also significantly higher than those in the bottom quartile (M = .05, SD = .30).

Discussion

We looked at participant’s confidence and accuracy on a psychological misconception test to measure whether these two variables were related. We found that confidence does not significantly correlate with accuracy. Participants who were low on accuracy and high on accuracy showed about the same amount of confidence, which is what would be expected for a Dunning-Kruger effect curve. In a Dunning-Kruger curve, confidence is high in the bottom quartile of expertise of the content and high in the top quartile. The typical Dunning-Kruger curve dips low in confidence in the middle two quartiles of expertise of the content. We found that the people in the middle of accuracy on the misconceptions test were also just as confident as everyone else. This lack of statistical significance between confidence and accuracy shows practical significance. Participants showed the same level of confidence in their answers, no matter how accurate they were on the test. This means that people may not know when they are wrong with regard to psychological misconceptions.

Next, we looked at individual differences of participants by separating them into quartiles of accuracy. We measured whether participants in different quartiles of accuracy varied on their confidence difference score. We found that participants who were in the top 25% of accuracy were significantly different from participants of all other quartiles of accuracy. The participants who were the most correct were also the most likely to know when they were incorrect and change their confidence to reflect their lack of knowledge. Overall confidence in wrong answers went up with the more wrong answers a participant answered. So that those who were in the bottom 25% of accuracy were the most likely to show more confidence in their wrong answers than their correct answers.

Study Implications

Psychological misconceptions studies have focused primarily on the undergraduate population because this is where students can potentially change their inaccurate beliefs (Bensley, Rainey, Lilienfeld & Kuehne, 2015; Best, 1982; Brown, 1983; Gardner & Dalsing, 1986). Studying the Dunning-Kruger effect along with misconceptions adds new understanding to this research. Because each student holds different misconceptions it may be useful to teach how we can all have confidence in misconceptions without accuracy.

In a study of the effect of education on psychological misconceptions, they tested belief in psychological misconception at the beginning of an introductory psychology course and at completion. Students showed 38.5% accuracy on the myths test at pretest and 66.3% accuracy at post-test. This indicates that some education can affect misconceptions, but students are still ending their psychology classes with many misconceptions still intact (Taylor & Kowalski, 2004). Kowalski and Taylor (2009) suggest that directly refuting the misconceptions may be the most useful thing for changing misconceptions. This method required teachers to know the misconceptions and take the time to present each one with the scientifically supported facts. This method may be time-consuming and tedious. However, other research has noted that the more familiar people are with inaccurate information the more they are likely to remember the inaccurate information even when it is presented with accurate information, simply because the inaccurate information feels more familiar (De keersmaecker & Roets, 2017).

In our study of psychological misconception, we have found that overall confidence in these misconceptions is high and it is even higher the more that someone doesn’t know. This means that many students come into psychology courses with confidence in their inaccurate knowledge and this can be difficult to change. Instead of trying to change a student’s misconceptions one misconception at a time it could prove useful to use this study as an example to students, that we can all have confidence in psychological misconceptions. The current study may be used as an example to teach in the classroom for teachers to meta teach about thinking instead of focusing on individual misconceptions. Looking at this study may help students to question their own knowledge or lack of knowledge and to understand why it is important to seek knowledge from scientifically supported sources.

References

Arntzen, E., Lokke, J., Lokke, G., & Eilertsen, D.-E. (2010). On Misconceptions About Behavior Analysis Among University Students and Teachers. Psychological Record, 60(2), 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03395710

Bensley, D. A., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2015). What Is a Psychological Misconception? Moving Toward an Empirical Answer. Teaching of Psychology, 42(4), 282–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628315603059

Bensley, D. A., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2017). Psychological Misconceptions: Recent Scientific Advances and Unresolved Issues. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(4), 377–382. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417699026

Bensley, D. A., Lilienfeld, S. O., & Powell, L. A. (2014). A new measure of psychological misconceptions: Relations with academic background, critical thinking, and acceptance of paranormal and pseudoscientific claims. Learning and Individual Differences, 36, 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2014.07.009

Bensley, D. A., Rainey, C., Lilienfeld, S. O., & Kuehne, S. (2015). What do psychology students know about what they know in psychology? Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 1(4), 283–297. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000035

Best, J. B. (2016). Misconceptions about Psychology among Students Who Perform Highly: Psychological Reports. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1982.51.1.239

Brown, L. T. (1983). Some More Misconceptions About Psychology Among Introductory Psychology Students. Teaching of Psychology, 10(4), 207. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328023top1004_4

De keersmaecker, J., & Roets, A. (2017). ‘Fake news’: Incorrect, but hard to correct. The role of cognitive ability on the impact of false information on social impressions. Intelligence, 65, 107–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2017.10.005

Furnham, A. (1992). Prospective psychology students’ knowledge of psychology. Psychological Reports, 70(2), 375. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1992.70.2.375

Furnham, A., & Hughes, D. J. (2014). Myths and Misconceptions in Popular Psychology: Comparing Psychology Students and the General Public. Teaching of Psychology, 41(3), 256–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628314537984

Gardner, R. M., & Brown, D. L. (2013). A test of contemporary misconceptions in psychology. Learning & Individual Differences, 24, 211–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2012.12.008

Gardner, R. M., & Dalsing, S. (1986). Misconceptions about psychology among college students. Teaching of Psychology, 13(1), 32–34. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328023top1301_9

Hughes, S., Lyddy, F., & Kaplan, R. (2013). The impact of language and response format on student endorsement of psychological misconceptions. Teaching of Psychology, 40(1), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628312465861

Kolodziejski, L. R. (2014). Harms of hedging in scientific discourse: Andrew Wakefield and the origins of the autism vaccine controversy. Technical Communication Quarterly, 23(3), 165–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2013.816487

Kowalski, P., & Taylor, A. K. (2009). The effect of refuting misconceptions in the introductory psychology class. Teaching of Psychology, 36(3), 153–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/00986280902959986

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121

Lilienfeld, S. O., Lynn, S. J., Ruscio, J., & Beyerstein, B. L. (2010). 50 great myths of popular psychology: Shattering widespread misconceptions about human behavior (2009-17191-000). Wiley-Blackwell.

Pennycook, G., Ross, R. M., Koehler, D. J., & Fugelsang, J. A. (2017). Dunning–Kruger effects in reasoning: Theoretical implications of the failure to recognize incompetence. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 24(6), 1774–1784. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-017-1242-7

Taylor, A. K., & Kowalski, P. (2014). Student misconceptions: Where do they come from and what can we do? In V. A. Benassi, C. E. Overson, & C. M. Hakala (Eds.), Applying science of learning in education: Infusing psychological science into the curriculum. (2013-44868-021; pp. 259–273). Society for the Teaching of Psychology.

Taylor, A. K., & Kowalski, P. (2004). Naïve Psychological Science: The Prevalence, Strength, and Sources of Misconceptions. The Psychological Record, 54(1), 15–25.