Does Distance Education Contribute To Inequity? A Critical Look at Current Issues and Potential Solutions?

Abstract

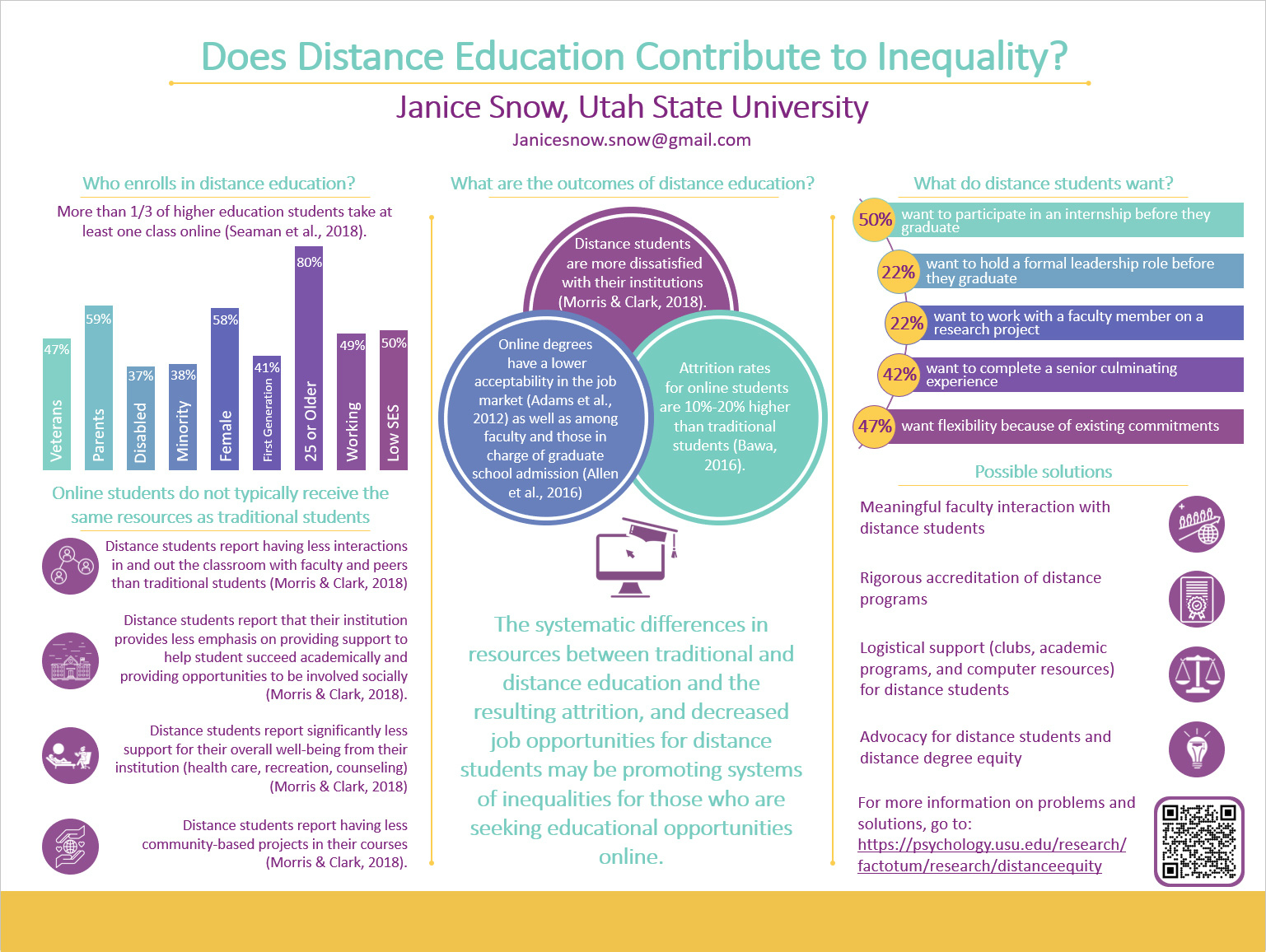

While the concept of distance education provides the same theoretical promise of potential, online students do not typically receive the same resources as traditional students (such as computer labs, counseling services, etc.). Meaningful interaction with faculty and peers, honors societies, clubs, research and service-learning opportunities, academic and logistical support are not commonly available to online-only students to the same degree as traditional students. These limitations may account for the lower retention rates of online students (Bawa, 2016). Distance education degrees are at a disadvantage in the job market because they have shown to have less acceptability by employers (Adams et al., 2012). Given that distance-only students make up a differential demographic than traditional students, including higher rates of women, people with disabilities, individuals with lower SES, and those with families (Best Colleges, 2018), these systematic differences in resources while in school that may support retention, and job opportunities while outside of school that may support job prospects may be promoting systems of inequalities for those who are seeking educational opportunities. Potential solutions are discussed.

Keywords: distance students, online students, resources, attrition, inequalities

Does Distance Education Contribute to Inequity?

Literature Review

Distance higher education has been around for decades and has been evolving and changing with the advent of new technologies. Online education is what most distance education is today. Online education has been defined as education that uses “the internet as the delivery mechanism for at least 80% of the course content” (Kentnor, 2015). Distance education in all its forms was created with the goal that it would open doors of education to individuals who may not be able to attend traditional face-to-face classes. It has been suggested that distance education would create a “revolutionary solution to diverse educational problems of inequality” (Lee, 2017).

In 2007, 21.4% of higher education students were enrolled in at least one online class. By 2012 that number had grown to 32.5% of students taking at least one online class (Kentnor, 2015). With over one-third of higher education students taking at least one online class, online students don’t represent a homogeneous sample. Some students take one online class and others take fully online degree programs. Undergraduate students make up the majority of the distance education population but 17.38% of distance students are graduate students (Seaman et al., 2018). Married, female, full-time employed and parent students are more likely to enroll in some online courses or a fully online degree program (Ortagus, 2017). Veterans are more likely to enroll online (Radford, 2011), as well as minority, low SES, first-generation students and students with disabilities (Best Colleges, 2018).

Students who are prepared academically and financially to engage in online education are more likely to succeed. Minority students, low SES, and those lacking the academic skills needed tend to need extra help. The convenience of online education is appealing to those students who are disabled and would struggle to get to or participating in face-to-face classes. The online education environment may be more difficult for those students who need extra help and resources but often cannot attain that help (Lee, 2017; Linder et al., 2015).

Meaningful interaction with faculty and peers, honors societies, clubs, research and service-learning opportunities, academic and logistical support are not commonly available to online-only students to the same degree as traditional students. In the national survey of student engagement, distance students report having fewer interactions in and out of the classroom with faculty and peers (such as study groups, collaborating on research, discussing academic and career goals) than traditional students. They perceive less quality engagement with fellow students, faculty, and student service staff (career services, student activities, etc.). Online students reported that their institution provided less emphasis on providing support to help students succeed academically, attending campus activities and events, using learning support services, providing opportunities to be involved socially, and encouraging engagement with students from diverse backgrounds than traditional students reported. Distance learners perceive significantly less support for their overall well-being from their institution (health care, recreation, counseling) compared to traditional students. They also report having less community-based projects (service-learning) than traditional students (Morris & Clark, 2018).

These resources are offered in the university setting because they contribute to student success. For example, one study found that meaningful faculty interaction for traditional students both in research and within the classroom have shown to contribute to higher GPA’s, acceptance into graduate school, and in increasing critical thinking skills (Kim & Sax, 2009).

Distance education’s lack of equitable resources may account for the lower retention rates of online students. Attrition rates for online students are 10%-20% higher than traditional students (Bawa, 2016). Holding an online degree may also prove to be detrimental after distance students graduate. Online degrees have lower acceptability in the job market (Adams et al., 2012) as well as among faculty and those who are in charge of graduate school admission (Allen & Seaman, 2016).

Conclusion

Distance students represent a differential student demographic than traditional face-to-face students. This includes higher percentages of individuals who may already be marginalized in society and the job market such as women, people with low SES, Individuals with disabilities, veterans, and minorities. With the resulting attrition, lower rates of acceptability in the job market and graduate school admission, distance education may be creating a predictably biased and inequitable market. We are increasing income inequality through online education.

Solutions

Inequality in distance education can be solved if those who are involved do not rely on diffusion of responsibility. Advocating and making the changes for distance students now is how we can fix this problem. Distance education should not be offered unless there are logistical supports offered to give equitable experiences. Such as honors societies, clubs, academic support, interaction with peers, training, mental health counseling, Computer resources, student unions, social events, as well as integration and drop-out support. By providing opportunities for distance students to have more interaction with faculty and mentors inside and outside of the classroom students may be more successful in the present and future.

Not all online degree programs and institutions are as rigorous as traditional degree programs. We need to increase rigor in the accreditation of online degrees. Because some institutions and programs lack accreditation rigor, this gives all online degree programs a bad reputation and leads to the increased unacceptability of online degrees by employers and educators.

References

Adams, J., Lee, S., & Cortese, J. (2012). The Acceptability of Online Degrees: Principals and Hiring Practices in Secondary Schools. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 12(4), 408–422. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/38477/

Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2016). Online Report Card: Tracking Online Education in the United States. In Babson Survey Research Group. Babson Survey Research Group. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED572777

Bawa, P. (2016). Retention in Online Courses: Exploring Issues and Solutions—A Literature Review. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2158244015621777

Best Colleges. (2018, February 23). 2019 Online Education Trends Report. BestColleges.Com. https://www.bestcolleges.com/research/annual-trends-in-online-education/

Kentnor, H. E. (2015). Distance Education and the Evolution of Online Learning in the United States. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Distance-Education-and-the-Evolution-of-Online-in-Kentnor/9fcd8875bcdac7f213d7672d7be3883b9a335b2b

Kim, Y. K., & Sax, L. J. (2009). Student–Faculty Interaction in Research Universities: Differences by Student Gender, Race, Social Class, and First-Generation Status. Research in Higher Education, 50(5), 437–459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-009-9127-x

Lee, K. (2017). Rethinking the accessibility of online higher education: A historical review. Internet & Higher Education, 33, 15–23. https://doi-org.dist.lib.usu.edu/10.1016/j.iheduc.2017.01.001

Linder, K. E., Fontaine-Rainen, D. L., & Behling, K. (2015). Whose job is it? Key challenges and future directions for online accessibility in US Institutions of Higher Education. Open Learning: The Journal of Open and Distance Learning, 30(1), 21–34. https://doi-org.dist.lib.usu.edu/10.1080/02680513.2015.1007859

Ortagus, J. C. (2017). From the periphery to prominence: An examination of the changing profile of online students in American higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 32, 47–57. https://doi-org.dist.lib.usu.edu/10.1016/j.iheduc.2016.09.002

Radford, A. W. (2011). Military Service Members and Veterans: A Profile of Those Enrolled in Undergraduate and Graduate Education in 2007-08. Stats in Brief. NCES 2011-163. In National Center for Education Statistics. National Center for Education Statistics. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED524042

Seaman, J. E., Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2018). Grade increase: Tracking distance education in the United States. Wellesley: The Babson Survey Research Group. http://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/highered.html